Sustainable Development Goals

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals provide a widely recognized framework for understanding the social, environmental, and economic challenges shaping our world. World Expeditions Schools educational journeys naturally connect with these goals and reflect curriculum priorities valued by North American schools.

Our programs give teachers clear, practical ways to extend classroom learning into real world contexts through experiential education offered across a range of international settings. Students engage directly with communities, environments, and systems, applying learning from science, humanities, geography, civics, and leadership frameworks. This approach allows teachers to meet curriculum expectations while giving students meaningful learning experiences that build critical thinking, global awareness, and responsibility.

Contact us to discuss how an overseas school program can support your curriculum goals.

SDG 1 – No Poverty

Eliminate poverty in all its forms everywhere.

Mapped to IB Individuals and Societies, AP Human Geography, and Common Core social studies and literacy outcomes, learning experiences connected with SDG 1 examine how education, livelihoods, infrastructure, and local decision making influence economic stability and community resilience. Students explore poverty as a complex system shaped by geography, resources, policy, and opportunity. Activities may include contributing to school-based initiatives, working alongside community organizations and trained builders, engaging with sustainable farming practices, and evaluating how community-led economic projects improve living conditions and create longer-term pathways toward financial security. Teachers often choose to discuss program ideas with an education travel specialist early in the planning process.

SDG 2 – Zero Hunger

End hunger, achieve food security, improve nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture.

Connected to NGSS, AP Environmental Science, AP Biology, and IB Sciences, learning experiences related to SDG 2 investigate how food systems, nutrition, agriculture, and environmental conditions interact. Through hands-on, community-based learning, students examine food insecurity and the role of sustainable agriculture in improving nutrition and long-term resilience. Experiences may include collaborating on sustainable farming practices, exploring composting and soil health, preparing food using locally sourced ingredients, and analyzing how agricultural systems respond to environmental pressures.

SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-being

Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages.

Relevant to NGSS, AP Biology, AP Environmental Science, and health and social studies frameworks, learning experiences linked with SDG 3 explore how clean water, sanitation, nutrition, environment, and basic infrastructure shape community health and well-being. Students engage with initiatives focused on clean water access, improved sanitation, reduced indoor air pollution, sustainable food systems, and care-focused service activities. These experiences help students understand health as an interconnected system influenced by environmental, social, and economic factors.

SDG 4 – Quality Education

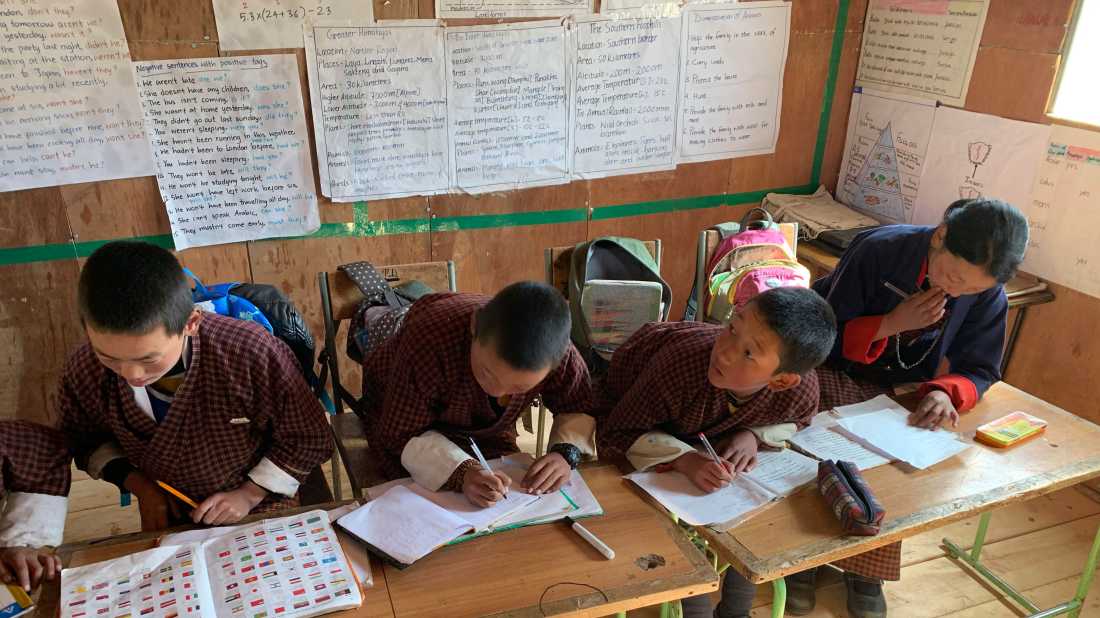

Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all.

Aligned with Common Core literacy and social studies, IB Approaches to Learning, IB CAS, and Duke of Edinburgh, learning experiences associated with SDG 4 examine how access to education, learning environments, and community support influence opportunity and long-term outcomes. Students explore barriers to education and contribute to initiatives that strengthen school infrastructure, enhance learning resources, and improve inclusive access. These experiences reinforce the role of education in building resilient communities and supporting lifelong learning. Teachers planning these experiences often speak with us about aligning activities to specific curriculum goals.

SDG 5 – Gender Equality

Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls.

Informed by IB Individuals and Societies, AP Human Geography, Common Core social studies, and IB CAS, learning experiences connected with SDG 5 explore how gender equity, education, health, and economic participation influence community well-being. Through community-based initiatives, students engage with projects that promote women’s leadership, vocational skills, economic participation, and health-focused infrastructure. These experiences allow students to examine structural barriers while applying classroom learning to inclusive, real world contexts.

SDG 6 – Clean Water and Sanitation

Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.

Linked to NGSS, AP Environmental Science, AP Biology, and geography curricula, learning experiences related to SDG 6 examine how clean water access, sanitation systems, and sustainable water management underpin public health and community resilience. Students engage with clean drinking water initiatives, sanitation improvements, hygiene education, and freshwater conservation, building an understanding of how environmental systems connect to human health and development.

SDG 7 – Affordable and Clean Energy

Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all.

Related to NGSS, AP Environmental Science, physics, and geography, learning experiences connected with SDG 7 explore how renewable energy systems, energy efficiency, and clean technologies contribute to sustainable development. Students investigate renewable power generation, off grid energy systems, and energy infrastructure, applying classroom concepts to practical energy challenges while examining links between energy, climate, and community resilience.

SDG 8 – Decent Work and Economic Growth

Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all.

Framed around IB CAS, AP Human Geography, economics, business studies, and social studies, learning experiences linked to SDG 8 explore how ethical enterprise, skills development, and community-led initiatives create sustainable livelihoods. Students examine vocational training, microenterprise, and locally driven economic models, gaining insight into how inclusive economies support long-term community resilience.

SDG 9 – Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure

Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation.

Relevant to AP Human Geography, STEM, design and technology, and social studies, learning experiences associated with SDG 9 focus on how infrastructure, innovation, and sustainable design contribute to long-term community development. Students explore construction projects, water systems, and low impact technologies, examining how traditional knowledge and modern innovation combine to create resilient infrastructure. If you would like to explore how these themes could fit within your program structure, you can talk with an expert.

SDG 10 – Reduced Inequalities

Reduce inequality within and among countries.

Connected to IB Individuals and Societies, AP Human Geography, civics, and social studies, learning experiences related to SDG 10 explore how inequality affects access to education, resources, and opportunity. Through ethical, community-based engagement, students examine inclusive approaches that reduce disparities and strengthen marginalized communities.

SDG 11 – Sustainable Cities and Communities

Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable.

Aligned with IB Individuals and Societies, AP Human Geography, civics, and geography, learning experiences connected with SDG 11 explore how communities plan, build, and care for places. Students examine sustainable housing, infrastructure, transport, and cultural heritage, developing an understanding of how inclusive planning improves quality of life in both urban and rural settings.

SDG 12 – Responsible Consumption and Production

Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns.

Related to NGSS, AP Environmental Science, geography, economics, and sustainability studies, learning experiences associated with SDG 12 examine how resource use, waste reduction, and production systems affect environmental and human systems. Students explore circular economy principles, sustainable food systems, and conservation practices through applied learning.

SDG 13 – Climate Action

Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.

Aligned with NGSS, AP Environmental Science, geography, and climate science, learning experiences connected with SDG 13 focus on climate systems, human impact, and adaptation strategies. Students engage in ecosystem restoration, sustainable land management, and climate resilient practices, applying classroom science to real world environmental challenges.

SDG 14 – Life Below Water

Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas, and marine resources for sustainable development.

Relevant to NGSS, AP Environmental Science, marine biology, and geography, learning experiences linked with SDG 14 explore ocean systems, marine biodiversity, and conservation. Students engage in reef monitoring, restoration, and marine stewardship activities, building understanding of how healthy oceans support resilient coastal communities.

SDG 15 – Life on Land

Protect, restore, and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems.

Learning experiences associated with SDG 15 give teachers practical ways to teach environmental science, geography, and sustainability through hands-on ecosystem work. Students engage in conservation, reforestation, wildlife protection, and sustainable land management, developing ecological literacy, systems thinking, and scientific inquiry skills. Teachers frequently contact our team to map these experiences to school priorities.

SDG 16 – Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions

Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development.

Connected to Common Core literacy, civics, social studies, global studies, and IB Individuals and Societies, learning experiences related to SDG 16 explore governance, justice, ethics, and social responsibility through community-based learning. Students examine inclusive decision making, education access, and cultural preservation, developing critical thinking and global citizenship skills.

SDG 17 – Partnerships for the Goals

Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize global partnerships.

Learning experiences connected with SDG 17 help teachers demonstrate how meaningful change occurs through collaboration. Students work alongside community organizations, NGOs, schools, and local leaders, developing communication, teamwork, and problem solving skills while gaining insight into how partnerships strengthen communities and support sustainable outcomes.

Contact us to plan your next overseas school program.